“I Don’t Think We Should Be Vaccinating Everybody” — Theoretical Epidemiologist Prof. Sunetra Gupta

Watch ➥ Odysee | Rumble | BitChute | Brighteon | Minds | YouTube | Archive

Professor Sunetra Gupta

Sunetra Gupta is Professor of Theoretical Epidemiology in the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford, and a Royal Society Wolfson Research Fellow. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Princeton University and a Ph.D. from the University of London. She has been awarded the Scientific Medal of the Zoological Society of London, the Royal Society Rosalind Franklin Award, and currently holds a Royal Society Wolfson Research Fellowship and an ERC Senior Investigator Award.

In addition to epidemiology she has expertise in immunology, vaccine development, and mathematical modeling of infectious diseases. Her area of specialization is evolutionary ecology of infectious disease systems.

Sunetra gave this talk to the COVID Plan B group which opposes the official narrative of the deadliness of Covid-19 and its continuous new strains, the necessity of the lockdowns and the theory of elimination, and instead proposes treating the coronavirus like the seasonal flu (using vaccines).

Transcript

Host ➝ 00:00

I’d like to introduce Senetra Gupta. She’s a theoretical epidemiologist from Oxford University. She spoke at our first symposium back in August last year which turned out to be the most popular clip on our YouTube channel. Tens of thousands of people have watched that clip and from there on Sunetra has kept speaking, and talking about what she sees and keep doing her analysis. Very grateful that she can join us again today. Sunetra, are you there with us?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 00:36

I am, indeed. Yes. Pleasure to be here. Thank you for asking me back.

Host ➝ 00:48

I’m very glad we’re honored. We’re very glad to have you back with us despite everything that’s happened. But we can talk a little bit more about that afterwards. So I’d like to invite you to shoot away with your presentation if you’d like.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 01:05

Okay, can I, I can share my screen. Yes, that’s possible. There we go.

And I’ve got to try and find it, oops. Get the slideshow. Oh, there we go. Right. Okay. Right.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 01:35

So you know, I’m going to try and keep this short. I used to have this as my final slide, but now I’ve started to give talks with this as my first slide, which is just to say the starting point, really, for all of us in thinking about how to cope with this situation is that we cannot afford lockdowns.

So that’s true in many parts of the world, and I believe is also true in the UK. Lockdowns are a luxury that only the affluent within an affluent country can actually afford.

As my colleague Martin Kulldorff recently put it, lockdowns are like focus protection for the liberal elite essentially. And they protect those of us who can conduct our business through laptops and Zoom and whatnot, and have some gardens that allow us to accommodate our children and others we care about.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 02:42

But they are absolutely disastrous at every level for the poor and the young, both in the global North and the global South. And actually one of the projects I’ve been involved with in initiating since I last spoke is called Collateral Global, where we seek to, we’re trying to develop a global repository for research into the collateral effects of COVID-19 lockdown measures.

And when we say effects, we do, we are going to actually look at both positive and negative effects, but we do think it’s very important to have these in focus before you can develop any kind of rational policy.

So also what’s happened, although I may have actually shown you this slide in August is, is that some of us have got together and various groups have got together to look at other solutions.

And the one that I’ve been advocating is one of focus protection whereby we shelter the vulnerable specifically, which is something that is afforded to us by the nature of COVID-19, in that it is, there is a clearly identifiable group of people who are vulnerable to severe disease and death.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 04:07

And in October Jay Bhattacharya, who’ll be speaking as well, and Martin Kulldorff and I got together and produced something we call the Great Barrington Declaration, which has put forward this idea and try to flesh it out as as a sort of policy document and has attracted attention, both negative and positive, since then.

So the idea is to take advantage of two things. One that the pathogen acts in such a ways we can identify who is vulnerable and who’s likely to die, which is mainly the elderly and the frail, but also those with certain comorbidities.

“Lockdowns are, like focus protection for the liberal elite essentially… they are absolutely disastrous at every level for the poor and the young”

What this allows us to do is to protect the rest of the population from the harms of lockdown, and which also allows immunity to accumulate in the population, what we used to call – hopefully we’ll continue to call – herd immunity, despite it suddenly having become this rather dirty word.

So this is possible if you shelter the vulnerable and allow the the rest of the population to function. Normally we recommended that we invest on, of course, in therapy and vaccination, particularly since vaccination is a means of protecting the vulnerable. And that’s indeed what we now have with the array of vaccines at our disposal.

And one of the other things that I thought was missing from the debate and continues to be missing from the debate is that we need to think outside national boundaries and consider our responsibilities as international citizens in dealing with this solution.

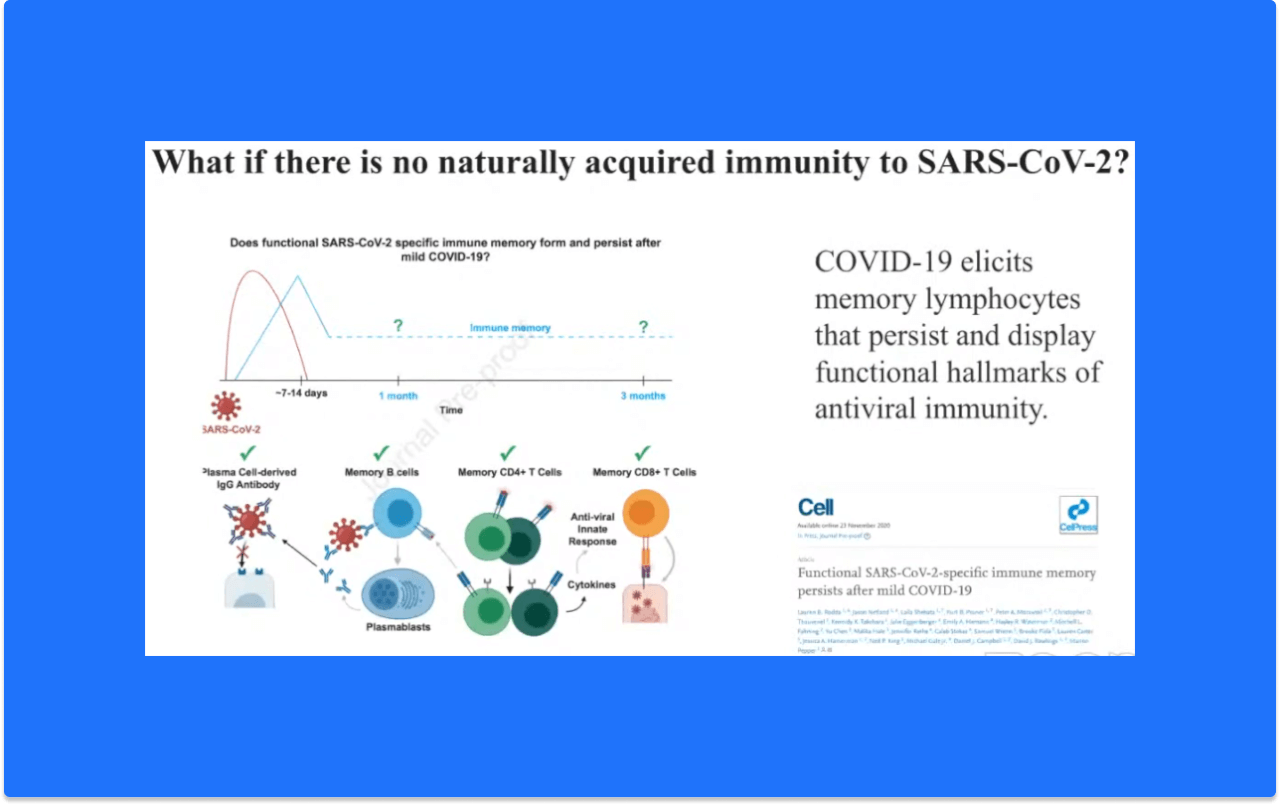

So of course, this was met with a barrage of criticisms and the of these is what if there is, which was put forward by people who thought we were somehow advocating something that would kill a lot of people. And the first objection was what if there is no naturally acquired immunity to this SARS-CoV-2 which is a virus that causes COVID-19 and that we know is simply not true.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 06:19

There was no reason for us to think there’ll be no naturally acquired immunity to this virus. It belongs to family of other coronaviruses for which we have ample evidence that there is naturally acquired immunity.

And now we know, now that so much time has elapsed, we have been able to do studies, which confirmed that COVID-19 elicits a long-term immunity.

This is not always evident in whether people have antibodies in their blood at the time they’re sampled, those could disappear, but the immune memory, the ability to fight the virus, particularly at the level of whether or not you come down with severe disease and die, is definitely retained.

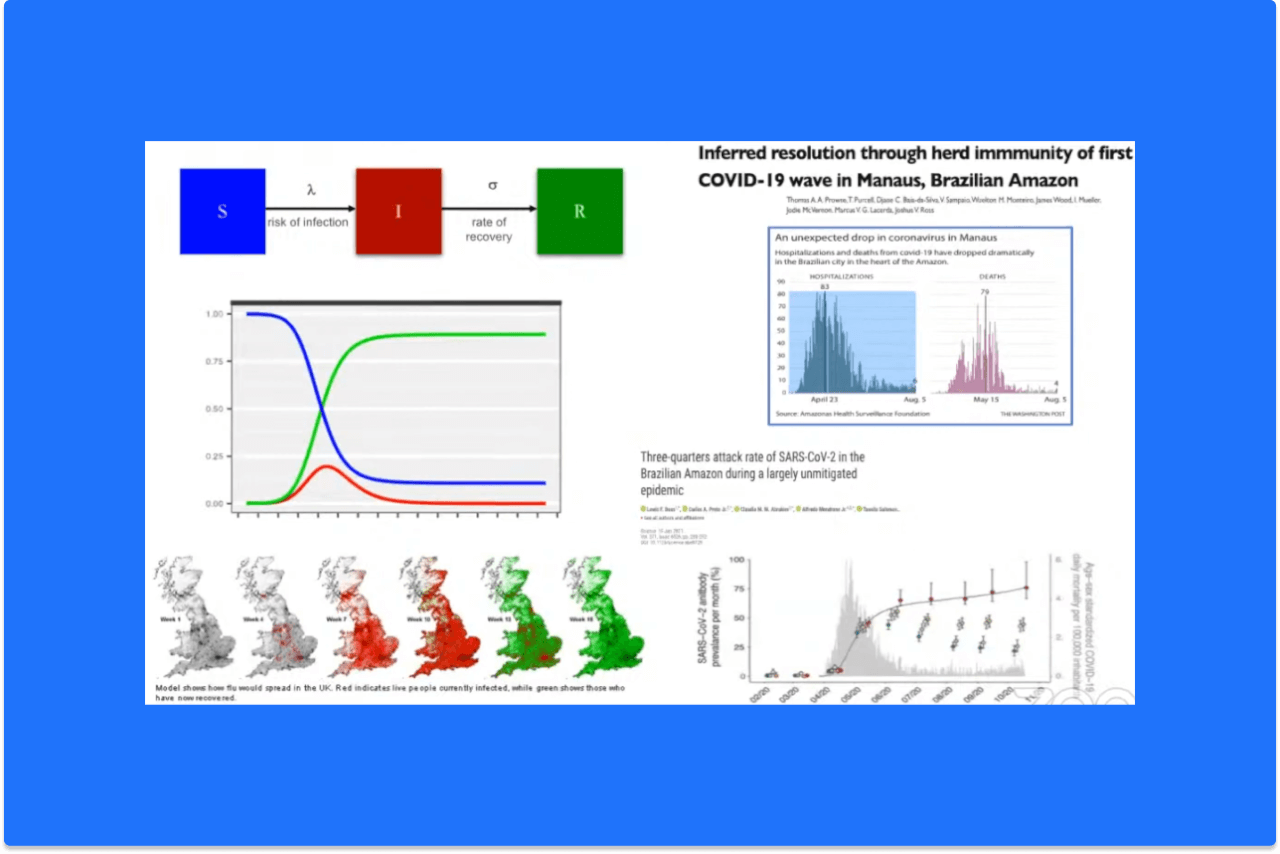

What that means is that we can continue to use this model, which is what is the basis of what most people use whether it’s in a very simple form or complicated computer simulation form, a fundamental framework known as the SIR framework is what people use to study the dynamics of COVID.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 07:33

And in this framework, people go from being susceptible to being infected and then recover, write down a set of equations or a computer simulation, and you get an epidemic where the accumulation of people in the recovered class who are immune, at least for the time being, causes the epidemic to turn over and start to die away.

This is something obviously that’s hard to, I mean, it’s hard to determine what the extent to which herd immunity has contributed to the decline in cases that we see worldwide, we’re seeing worldwide at the moment. Because of the interventions that we’ve also been putting in place.

“There was no reason for us to think there’ll be no naturally acquired immunity to this virus. It belongs to family of other coronaviruses for which we have ample evidence that there is naturally acquired immunity.”

But there are regions where it’s incontrovertibly been herd immunity that has resulted in the resolution of at least what people would call the first wave of the epidemic such as in Manaus in Brazil, and several papers have been published, showing both that the shape of the epidemic, the increase in deaths, hospitalizations and its subsequent resolution was accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of antibodies, an indication that a large number of people had been exposed to the virus.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 09:09

So this implies that herd immunity plays an important role in the control of this virus and that we can use it as a tool in trying and keeping the risk of infection low to those who are vulnerable. Since then, however, in Manaus, we have seen a resurgence of COVID-19 and the people, some of the authors of one of the papers that I just showed have within two weeks of publishing, the paper came, produced a commentary in which they suggested a number of reasons why this might be happening.

And one of these is that immunity against infection might already have begun to wane by December following the first wave in April. And this is also, it aligns with a concern that people have had in our focus protection hypothesis, in which herd immunity plays a role.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 10:15

What if herd immunity doesn’t last forever? Or what if it doesn’t last forever? Does that mean as some people have suggested that we can’t get to herd immunity. There are very good reasons to believe that it might not last forever because seasonal coronaviruses, other circulating coronaviruses, do not give you lifelong immunity in the way, for example, measles does.

The pattern there is that these current viruses existed a sort of endemic equilibrium where people keep getting reinfected, but reinfections carry with them very little risk of severe disease and death, which is why we don’t normally worry about coronaviruses.

So if that’s true of this coronavirus, how then can we think about herd immunity? Well, the truth is that whether immunity lasts forever or not, does not actually impact upon the buildup of maintenance of herd immunity.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 11:21

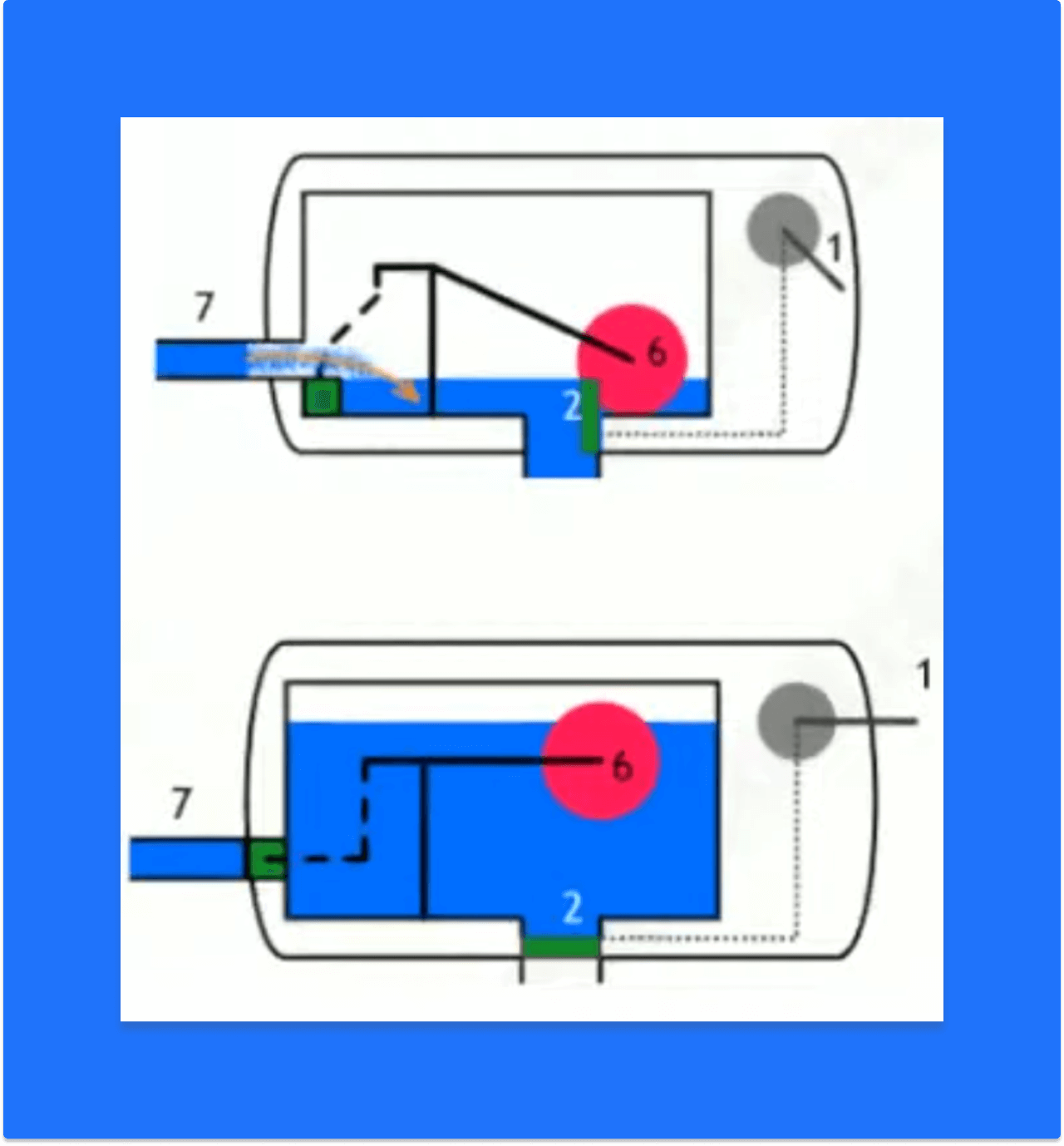

So you could have an SIR model in which people remain immune forever, or you can have what we call an SIRS model, which is probably the better metaphor for coronaviruses. And then where people go from being recovered, they lose their immunity and become susceptible again.

And in both cases, if you do the the mathematics, you’ll find that herd immunity is reached at a point where the proportion of immune in the population is at a particular threshold that’s determined by the fundamental transmission characteristics of the virus itself, which is reflected in this quantity R0.

And this is the same, that level at which everything settles, that what we would call an endemic equilibrium, the level of immunity in the population is the same for both the SIR and the SIRS.

“Circulating coronaviruses, do not give you lifelong immunity in the way, for example, measles does…”

In other words, the rate of loss of immunity does not influence the establishment or maintenance of herd immunity in contrast to many statements that were made.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 12:33

And the one that I’m showing you here is from an article in Nature, which is entitled the false promise of herd immunity which suggests that you’d never reach herd immunity through natural transmission if there is a rate of loss of immunity.

I often use this water cistern analogy to explain what’s going on here. Within a system a level of water is maintained at a constant.

It’s a constant level maintained, and this is independent of the rate at which water flows in and out. So measles would be a cistern in which water is flowing out very slowly, trickling out slowly as people die, and then you get new infections, newborns or people born into the population, filling up the system.

Coronavirus, little different, you get water flowing out quickly. People being reinfected and coming in. The system maintains the level through a more dynamic loss of water, loss of immune people, reinfections, but importantly, those reinfections do not carry with them a high risk of disease or death.

And therefore we still maintain the endemic equilibrium we want where the deaths are kept low.

The other thing that we know now is that previous exposure to other coronaviruses does give you some level of protection against, particularly against disease from the new virus. And so, in fact, the cistern, going by the system analogy, we didn’t actually start with an empty system with coronavirus.

“the truth is that whether immunity lasts forever or not, does not actually impact upon the buildup of maintenance of herd immunity”

And some work that my group, Jose Lourenco and Francesco Pinotti, have done shows that under those circumstances, the level of exposure required in a population to reach endemic equilibrium is much lower.

So we mustn’t confuse low observations of low prevalence of antibodies with – that does not mean that we haven’t reached a level where things have been kept in control by herd immunity.

Furthermore, once you factor in the effects of seasonality, you can start to find patterns that correspond entirely to what we’ve observed in many parts of the world in terms of an initial early peak and a seasonal increase at a later point in time.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 15:12

And these are just some simulations showing how the duration of immunity in combination with seasonality can give you those patterns. A paper published in Science a few months ago also reveals the same sort of dynamic occurring.

This is from Bryan Grenfell‘s group, again an SIRS model, but here they make the distinction again between being reinfected and infected for the first time, which allows you to see that you can easily replicate and understand what’s going on and where we’re headed in terms of a new virus coming in to which there was some immunity to a lot of immunity already to disease, some immunity to infection and how obviously that would cause an initial large peak, but then settled into this pattern whereby you get the infection levels sort of oscillate around an equilibrium due to seasonality and other considerations.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 16:18

So that could certainly be what underlies this recent increase in Manaus, but other explanations that the authors offered, which are pertinent to the current sort of discussion around what’s happening with SARS-CoV-2, is that there are new lineages emerging, and these may have properties that allow them to cause a second epidemic.

For example, there may have been a new lineage that occurred, and we know there are new lineages emerging in Manaus and in Brazil, which have a higher inherent transmissibility than pre-existing lineages. So this P.1 lineage is one of the variants of concern that’s emerged in Brazil that people are worried about now.

And there are several others that, you know, that’s why we’ve, UK has closed its borders and is obliging people to stay in quarantine. And apparently you can go to prison there for 10 years for lying about having gone to Portugal en route.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 17:24

And these are all predicated on this idea that some of these new variants that are arising are more transmissible. Are they?

Well, in order to understand this, we have to, again, we can employ the SIR framework, but this time we have to think about variation in the possible strains and variants of the virus.

And the simple answer is that indeed, it may well be that some of these variants are more transmissible, but the truth is that within a system where you have a lot of immunity shared amongst the variants, as you will have, because we know there’s strong cross responses, not just amongst variants of coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, but also amongst, within the whole coronavirus family.

What you tend to get under these circumstances is competitive exclusion. So the strain with the higher R0 wins, and then what that means is that even with the marginal increase in transmissibility, that could see a new variant sweep through, but that does not really have much of a material effect or difference in how we deal with the virus.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 18:38

In other words, the surge and the virus cannot be ascribed to a new variant, or it’s very improbable that the reason why we’re seeing surges is because the new variants are more transmissible.

On the contrary. What’s much more likely is the new variants are slightly more transmissible. And because they’re in a very competitive environment due to all the herd immunity that’s built up and because some of these mitigation methods, lockdowns also intensify the scramble for susceptible individuals, because of these circumstances, we are favoring variants that have only a marginal advantage in terms of transmissibility.

The other big question is are these variants more virulent? And the truth is that we don’t know, but it’s unlikely so far. The data don’t seem to say so despite these scary headlines.

And generally within these systems, what you have is a sort of trade off between virulence and transmission.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 19:43

So pathogens tend to evolve, but not always towards low virulence because that maximizes their transmissibility.

But generally what we’d expect a small variations in virulence and transmissibility, and one strain will probably emerge as the victor, but it’s very, it’s improbable. It’s not impossible, but it is much more probable that these trends will not be materially so different than we’d have to alter our policies.

In any case, the focus protection strategy kind of circumvents all these uncertainties by putting forward a proposal, which allows us to protect people and save them from severe disease or give them protection from severe disease and death, even if there were to be such a unusual, unlikely changes in the pathogen. The other final option that was considered by Sabino and colleagues is that which we’re all thinking about, is will these lineages, and are these new lineages able to evade immunity generated in response to previous infection?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 21:01

Is this an immune escape? Now that is worrying, of course, because at the moment, what we have, the best way of delivering focus protection is through vaccines. And so this is a question that we, that needs to be answered and people are answering, trying to answer it. And it’s clear and not surprising at all that some of these mutations, because they do happen to be in the very targets of immunity that actually are important for the virus to gain entry into cells, that some of these mutations are stopping or preventing the neutralization of the virus.

But there are a wealth of other targets on the virus, on the surface of the spike protein, and certainly natural infection gives you a whole array of other responses. So it’s unlikely to alter protection, at least against severe disease and death. It may compromise a protection against infection, but it’s not likely to alter protection against severe disease and death.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 22:09

So now we are back to this solution, we can refine it. We now have a good means, a very reliable way of sheltering the vulnerable by using all these vaccines that have been developed so quickly. So remarkably well. Because these vaccines, one thing we know, we can be sure of, is no matter how much mutation there is, and whatever else happens, that they’re very likely to protect, continue to protect against severe disease and death. And that’s what we want.

We have no idea even without mutation, how well they work against infection. And so it’s not a good, it’s not sensible to think of these vaccines as giving us herd immunity against transmission in the way that measles vaccines can do. So I think we’re going to have to rely on naturally acquired herd immunity in combination with vaccine induced protection, focus protection of the vulnerable in order to provide a global solution to the problem.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 23:17

And once again, in doing that, we need to, instead of closing borders, try and think outside national boundaries. In the end, I hope we will achieve a solution which combines our considerations of not just an understanding the logos, if you like, of this pathogen, how the science, as people like to call it, how it spreads and how immunity accumulates, how to make vaccines, but also to integrate into that what we do as human beings, considerations of pathos, in other words, socioeconomic environment considerations as well as ethos, how do we want to live our lives?

Thank you very much.

Host ➝ 24:02

Thanks, Sunetra. So you’ve got some time for some questions.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 24:08

Yes. I do.

Host ➝ 24:09

Yep. Okay. Thank you. I think, probably just, I’m going to pick up on the last point you made, and it was the one that right at the start, and it is one that you mentioned in the first presentation and that’s about the national boundaries because it’s something that wasn’t being touched on at the time and really still hasn’t.

One of the effects of COVID-19 and government responses has been nationalization with the latest of which we’ve seen as in the fight over vaccines. How might things have been different? One of the things that struck us has been every country seems to talk about its own battle with COVID and focus on their own responses and whether or not they’re being successful. It doesn’t appear as if we are learning well enough from each other. Comment on that.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 25:12

Yeah. I think it’s astonishing. I mean, I’ve been astonished right from the start at the lack of international perspective here, and a dereliction as I feel of our duties as international citizens, which I believe we have a, you know, we signed up to all of this, partly, you know, some of us due to our principals, some of us, because we thought it was how the global market appealed to them, I should say.

“It’s not sensible to think of these vaccines as giving us herd immunity against transmission in the way that measles vaccines can do. So I think we’re going to have to rely on naturally acquired herd immunity in combination with vaccine induced protection”

And so there were all these sort of, you know, their various from various perspectives, the idea that we were a global economy and, you know, all sorts of issues of internationalism, I thought had moved to very advanced stage where we couldn’t just go back to the sort of tribal kind of situation where we were only going to look after our national interests and gloat over, you know, having achieved something when it’s clearly at the expense of other countries who simply can’t afford it and are damaged by the policies that we’re adopting to protect foreign citizens.

Even if it is seen as the only way forward, I don’t think it should be something you should be proud of. You should be apologetic about having to protect you own citizens at the expense of the wellbeing of global citizens.

Host ➝ 26:38

Is that something that your Collateral Global effort is, counting the effects on say poor nations of withdrawals? Yeah. Okay.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 26:49

Yeah, no, that’s sort of the big focus of that project.

Host ➝ 26:54

I’m going to ask you just a couple of questions about trying to understand what I think you’ve been taking us through. It appears that what you’re saying, what you’ve summarized is this endemic equal equilibrium that SARS-CoV-2 is nothing out of the ordinary, that all of what we know is herd immunity and the fluctuations of the virus and the new strains, all of that is what we would expect to see under any coronavirus and that none of these new developments, if we call it that, are in themselves unusual or scary.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 27:31

Yes. I mean, I think it is a new phenomenon in that it has entered a population that has not, you know, what we’ve experienced is its epidemic phase.

And so one of the problems that I’ve encountered, one of the major sources of confusion is when people say, well, it’s not like flu, flu only kills, you know, 650,000 people a year, and that’s flu in its endemic state.

And COVID of course has gone through an epidemic phase in which it is likely to have a much higher death toll. Flu in an epidemic phase would kill very many more people. But what we can expect COVID to do is settle to an endemic state and what the focus protection plan offers is a way of getting to that endemic state without sacrificing, or sacrificing isn’t even the right word.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 28:30

We want to reach that state without allowing people to die. So if possible. And so what it does is offers a way of doing that. So if you protect the vulnerable, you shield them over that particular epidemic period.

And then when the epidemic period is over, they are no more vulnerable to corona, this particular virus than they are to other coronaviruses.

So that’s the idea is we take the risk, pull this risk back right down to the sorts of risks that we endure, that we are happy to accept as a society. So that’s where we should be. Well, it’s inevitable that we will head there.

But it’s a question, how do we get there? And the vaccine, of course, gives us a very useful route for approaching that, but what the vaccine won’t do, I don’t think, it doesn’t seem to have the ability to do – particularly in the face of mutating virus population, is it’s not going to give you protection against infection, which would allow us like measles to get to a state where of endemic equilibrium without… where people were protected against infection through vaccination, but that’s not going to happen.

All we can do with this vaccine at the moment is protect those who are vulnerable.

Host ➝ 30:07

Yeah. Okay. So you mentioned herd immunity that it’s become a dirty word or dirty phrase. How did something that was seen such as simple pass of epidemiology become demonized? How and why, do you think?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 30:24

Well, how I think is through confusion. So I think people assumed that herd immunity… well, it became a sort of a stand-in for a policy whereby you would allow the virus to just do its thing, let it rip as it were.

So it became interchangeable with that concept, which it isn’t because after all, I mean, herd immunity is just a phenomenon, whereas let it rip strategies is a decision on part of a government or a country or an individual.

That’s how it came to present to a certain group of people a policy that was unacceptable to them and carried connotations of not having any interest in the well-being of the elderly and the frail, which is rather unfortunate.

And generally speaking, I think the concept of herd immunity is misunderstood.

“One of the major sources of confusion is when people say, well, it’s not like flu, flu only kills, you know, 650,000 people a year, and that’s flu in its endemic state. And COVID of course has gone through an epidemic phase in which it is likely to have a much higher death toll. Flu in an epidemic phase would kill very many more people. But what we can expect COVID to do is settle to an endemic state.”

And that people assume that once you reach herd immunity, the disease goes away and that’s not true. Herd immunity as such simply refers to the protection that you gain from other people in your community being immune, and thresholds of herd immunity are ones which when crossed make the infection decline.

But generally speaking, where we end up is at that threshold, which is an equilibrium state where infections neither growth nor decline, except in some sort of seasonal way, which is just a sort of bobbing up and down around equilibrium.

So these concepts, which are not terribly difficult to take on board, but also very easy to misunderstand, particularly if you have a desire, some sort of political desire to misunderstand them, and that’s what’s led to this.

And that’s what you’re really asking is why and the why is a complex, but I’ve just been reading a very, a manuscript of proofs, a very good book by Toby Green, which will be coming out, I think, in April. And one of the things he says is that there were people who were rightfully so keen to get rid of characters like Trump and Bolsenaro that they just decided to politicize this whole thing in a way that’s been incredibly unhelpful and damaging to a lot of people.

Basically the politicization of this scientific dialogue has been to the detriment. And when I say detriment, we’re talking a serious detriment to many ordinary people.

Host ➝ 33:18

What sort of data has been provided by countries where they’ve experienced variants, that people are asserting a more virulent and/or transmissible. Have we, cause I think what I saw in your slides was that that’s not really there, that this doesn’t exist.

But we’re seeing headlines that claim it is in South Africa, claiming that, you know, that it’s one that the vaccine doesn’t handle it. But is the data there, have you seen it?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 33:49

So first of all, the data that have been misinterpreted and rather strangely by people who should be and are experts in the field, is that some of the variants, one of the one in Britain, for example, seems to be taking over from what was there before.

But as I explained, for something to take over, it doesn’t have to have hugely higher transmissibility. It’s just, you know, it’s a tug of war and, you know, you can attach a mouse to one end of the tug of war and pull the whole thing across to one side.

And that is more likely to be what happened then a large elephant having been attached to the other side. So there is no indicator… just because something is growing and taking over does not mean that it is hugely more transmissible and it’s sort of, it’s the inverse.

“Where we end up is at that threshold, which is an equilibrium state where infections neither growth nor decline, except in some sort of seasonal way, which is just a sort of bobbing up and down around equilibrium.”

Cases rose because of seasonality without any doubt. And within that rising cases, so there’s sudden expansion, the strain that was slightly more transmissible is very likely to expand more and take over very quickly. It doesn’t serve, it does not merit or what it doesn’t justify at all is the panic and the closure of borders surrounding that narrative. So I think the narrative is flawed and the worry – it doesn’t matter – anyone can come up with narratives and narratives. They are all somewhat flawed, but when a flawed narrative is used or an improbable narrative is used to inflict these sorts of conditions, then one has to really think about how it needs to be questioned.

Host ➝ 35:44

So I’m just trying to understand your presentation to me seems to be saying that the last year has been the rise of a pandemic, but if it hasn’t yet they’re settling back to some sort of endemic equilibrium. All of that was going to happen one way or another.

And everything we’ve seen has been heading towards that. And you’re saying that the best thing to have done was removed the most vulnerable and while the rest of us kind of, for lack of a better term, endure or be part of that settling down to the equilibrium.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 36:24

Yes, I think so. I mean, I think, I think that would, because, I mean, the main reason for that is that huge collateral damage that any other, I mean, so what can.

You can either suppress the infection or let it run its course and suppressing the infection is problematic for two reasons. One is that it’s a temporary measure. And secondly, because it has such a huge cost.

“The politicization of this scientific dialogue has been to the detriment. And when I say detriment, we’re talking a serious detriment to many ordinary people.”

So one option of course, that one could consider is we suppress the infection until we have a vaccine, even if that vaccine only protects the vulnerable population. So that’s, you know, a possible strategy, but in order to figure out whether that strategy is a viable one, you need to think about two things. One is how likely is there to be a vaccine, which has always been, you know, a big question mark, fortunately, now no longer a question mark. And the second question is can we afford to stay in lockdown until that event and for most areas, most parts of the world, the answer’s no. And yet it happened.

Host ➝ 37:42

Did we suppress the virus at all, though? And in any of these attempts, did the, and if we did, did that just change behavior of the virus?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 37:54

It’s very hard to say whether we were able to suppress the virus. I think it’s a question of, you know, how much lockdown is necessary. I mean, what’s the relationship between if there’s a scale of mitigation, severity of mitigation and success in suppressing the virus. I think that relationship is very non-linear.

So, but it’s very hard to say. In other words, what I’m saying is if you look at the trajectories in somewhere like Sweden or in the UK, the extent to… you can have two extremes in terms of explanations. You could say in one extreme, everything was just simply down to mandated or non-mandated non-pharmaceutical interventions and the other extreme, you can easily set up a model such as some of the ones I showed you where it’s all down to herd immunity and seasonality. Now the truth is going to be somewhere in between them.

And what I think, I don’t think we have the… we’re slowly starting to get the data that allows us to say where it actually lies, but what we need to do at the… the beauty of focus protection is that it says, it gives you a means of moving forwards, even with that uncertainty of which actually happened.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 39:22

So rather than engaging in some kind of academic battle or quibble over what worked and what didn’t work. I think what we need to do is keep very much focused on the costs of all of this and globally as global citizens and come up with ideas such as focus protection, which now we can deliver through vaccination and, you know, prevent ourselves from entering a situation. The head of the army in Britain wrote today saying this form of nationalism is going to create major instability.

And he’s worried that this could lead to, you know, a major war or a set of wars because that’s what nationalism leads to after all. Deprivation and nationalism, well, we know what happened a hundred years ago in the face of that – Germany.

So we have to be very careful and we are seeing all sorts of rules and laws being brought in, and a huge disregard for the suffering that’s been caused to children and to the poor.

So I think that we really need to move forwards with those things, ideas in mind and not ascribe them as people are doing now to the virus itself, but take responsibility for those, for the acts of mitigation having caused these harms.

Host ➝ 41:01

Yes, it’s something that’s certainly troubles me is that the approach over the past year has been the nationalism of it. But a lot of the the way it’s been conducted has been very unsettling and changing of the global environment, the global geopolitical situation. But we will be covering that with some of our other speakers.

I’ve got a big question to ask of you and I, and that’s about the Great Barrington Declaration. Something that I was very, I was very proud to see you do. It was a very, it was a brave thing. Can you describe, though, what it felt like afterwards? Did you attract the attention you expected? Did it do the job you wanted it to do?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 41:50

Well, I mean, and it attracted more attention than we expected, perhaps. I mean, there was, it’s certainly become part of the vocabulary of many of these debates. So, it certainly, and it gave people the license to express themselves, which, I mean, this has been a very sad part of all of this is, is finding people, finding that a lot of people are really afraid to speak out and this is really unfortunate. So it has given a platform to some people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to speak out. So those are all good things. But of course it’s been vilified and misrepresented. And at the moment it’s been weeks of relentless kind of ad hominem abuse that many of us have been suffering as a result of it.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 42:58

So now, of course, I feel that there was no choice, but to do this. And it was good because it arose independently. It was a bunch of people independently coming together to say this. So it wasn’t a group of people who know each other and review each other’s papers and all sort of saying, hey, let’s do this.

It really was, it’s quite life affirming to see bunch of people around the world who didn’t even know of each other’s existence coming together out of their convictions to put something together and have other people sign up to it.

So it’s certainly altered my life, but overall I’d say in positive ways. But it’s hasn’t really listened to it. Not in the UK, even though some people think that the UK delayed putting in harsher measures because of it, which is unfortunately not the case… so it’s not really had the effect, the desired effect on policy, but it has certainly had an effect on public opinion, I think, and giving people the space to think about all of this. I hope in a more nuanced way.

Host ➝ 44:34

Yes. So taking the the focus protection format and it’s the way the vaccines can fit in. Do you think that the perspective of yourself and ourselves and the Great Barrington, that can have an influence, that we can change the way that we settle back into an endemic equilibrium?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 44:57

Well, we were hoping very much that once these vaccines, now that they’re there, that, you know, I didn’t, I started to talk about the objections to the Great Barrington Declaration in terms of sort of biological facts like, is there herd immunity at all. But a very big kind of objection was that, how can you actually deliver focus protection, which is a, you know, a very valid point. That’s exactly what we wanted. We wanted a debate around that. There wasn’t a debate, it was more of an outright rejection.

You know, people laughing our faces, which seemed very odd because many of the ways that you would deliver focus protection are exactly what we do in lockdown anyway. It’s just restricted to a group of people rather than the whole population.

But we thought… we were hoping that the vaccine would give us a sort of a meeting point where focus protection could be delivered through the vaccine. And that would be the end of that. And those who said, well, we’re of the opinion that we should stay locked down until such a point arrives. I’m very happy to say that, yeah, maybe you’re right. I don’t mind.

What I really want now is for the children here to go back to school and for the damage that’s already been done to people’s lives to be limited. To go into mode of damage limitation, that the best we can hope for..

Host ➝ 46:36

Also one other question, if I may and that’s, that’s about vaccines again. So does, does MES vaccination, is that, is that necessary? Is that going to be the sticking points? Do you think it matters?

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 46:55

I think that’s going to be a problem. Yes, I agree. Because I think the way to use vaccines is to deliver focus protection. And I don’t think we should be vaccinating everybody. I think we should rely on a combination of focused protection through vaccination and naturally acquired immunity to provide with an absolutely solid impenetrable wall against this virus.

I also think that, you know, in a few years time, it may not even be that, you know, people will build up the immunity they need, that will see them through. Some people, you know, like people with comorbidities who aren’t succumbing to other coronaviruses are obviously not doing so because they’ve already been exposed to those coronaviruses at a time when they weren’t vulnerable. So, you know, the need for a vaccine will diminish with time, I think, but at the moment, it’s the most wonderful tool that we have to enact focus protection.

Sunetra Gupta ➝ 47:53

But we will, I think we’ll always need as we do with influenza at the moment you know, having herd immunity… if we did not have herd immunity in place for influenza, we would be in really serious trouble. And I think it’s very important that we allow that to occur.

“I don’t think we should be vaccinating everybody. I think we should rely on a combination of focused protection through vaccination and naturally acquired immunity.”

We should be grateful that we can allow herd immunity to accumulate without suffering losses of life, especially in the young, by protecting the elderly and the frail and the vulnerable, those with co-morbidities using a vaccine. And through other means as well.

I mean, maybe vaccination, won’t be the best, won’t be something that all vulnerable people can have. So, you know, we need to keep in place this idea that we must protect the vulnerable through vaccination and other means and bring the risks of infection down through herd immunity. And I think that’s the only way forwards.

“the need for a vaccine will diminish with time”

Host ➝ 49:01

Thank you, Sunetra. Really appreciate you joining us on a Friday evening and giving us your time again. Thank you. Bye, bye.

More Resources:

- Prof. Sunetra Gupta — New Lockdown is a Terrible Mistake

- Should Children Get Vaccinated? — Dr Fauci vs Dr Lavine

- New UK Coronavirus Variant Isn’t Even Worth a News Headline — Prof. Vincent Racaniello

Video Source https://www.covidplanb.co.nz/ (Copyright PLAN B International Covid Symposium: 2021, February 12 – Permission Obtained)